Preface: The Signal in the Noise

No matter which angle you take, Europe’s InfraTech moment has arrived. Since 2018 PT1 has been at the forefront of this shift, investing in technology that upgrades the physical world.

Over the years, we have consistently worked to bring the right people and the right ideas together.

Whether it was:

Our political initiative in early 2025, where we hosted federal ministers and party leaders at our HQ (a former substation) to discuss Europe’s path ahead of the German snap elections;

Joint efforts with founders, investors, and policymakers to help BESS achieve the breakthrough it deserves; or

Our early work to put climate adaptation firmly on the agenda.

Our objective has always been the same: to convene, to contribute & to help build the future Europe needs.

The article below marks the kick-off of our 2026 InfraTech campaign. It’s a collaborative effort that will unfold throughout the year with white papers, podcasts and thematic events across Europe.

We invite you to join the discussion, challenge us, and shape the agenda:

Where do you agree?

What did we miss?

How can we work together to make Europe resilient again?

Send us an e-mail, leave a comment on our page or send us a postcard! We look forward to a year of meaningful conversations and real action in 2026 and beyond.

Warm regards,

Your PT1 team

Executive Summary

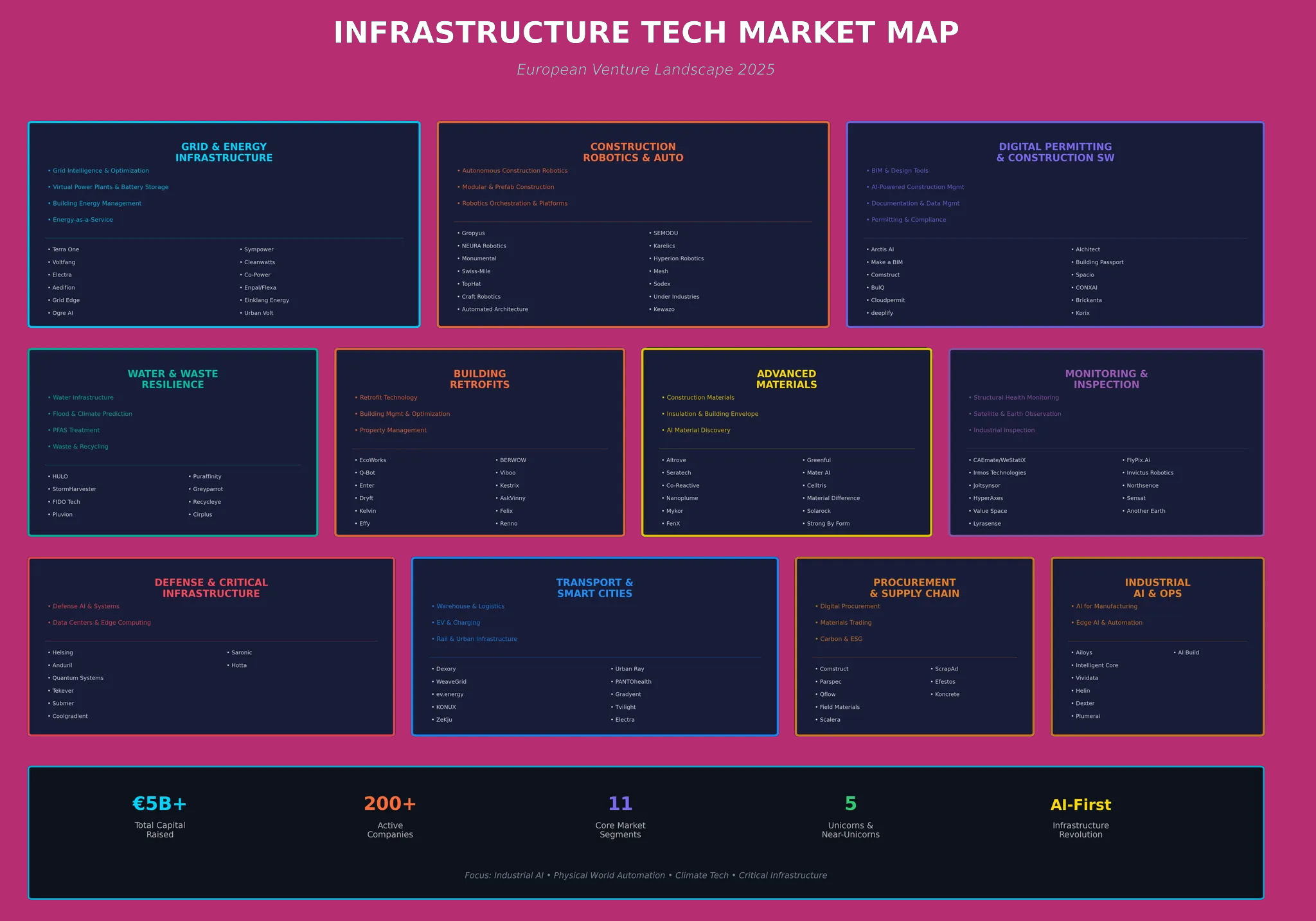

Europe faces a €6 trillion infrastructure transformation over the next decade, representing the largest since post-war reconstruction. The convergence of aging infrastructure, €2+ trillion in committed public funding and mature AI/robotics technology creates an unprecedented opportunity for InfraTech companies to emerge as the next generation of industrial champions. Private capital is already flowing, with companies like Hometree and Terra One proving that venture-backed startups can build and scale essential infrastructure. PT1, with its unique LP base of European industrial leaders and deep infrastructure expertise, is positioned to back the bold founders who will define this new era.

Why the next generation of industrial champions will be built in the coming years

A quiet transformation is unfolding across Europe. We say ‘quiet’ because most people have been looking in the wrong direction. For decades, infrastructure has been treated as the background fabric of society: the roads people drive on, the bridges they complain about, the pipes and grids and buildings that go largely unnoticed until they fail. But every major economic and political transition in modern history can be traced back to seismic shifts in these foundational systems. Today, those systems are simultaneously under strain at a level Europe has not seen since the post-war reconstruction era.

The reality should worry anyone who cares about Europe’s economic relevance and geopolitical stability. But for founders and investors who fully grasp the moment, this is the most significant industrial opportunity of the next decade, perhaps even the next generation. The convergence of collapsing physical infrastructure, political urgency, unprecedented funding, climate-driven disasters and new technology capable of operating in the physical world is reshaping the competitive landscape. And unlike in software, where incumbents often adapt, the incumbents here are structurally unfit to lead the new era.

The window is wide open. While it will remain open for years to come, the best opportunities are crystallizing right now.

1. Rethinking „Infrastructure“: The physical substrate of modern life

If you ask ten policymakers to define infrastructure, you will get ten different answers. Citizens think of roads and bridges, economists talk about public goods, VCs tend to avoid the topic altogether because it sounds slow, capital-intensive, and bureaucratic. None of these definitions are wrong technically, but all are insufficient.

Infrastructure today is best understood as the physical substrate of modern life. It spans six deeply interconnected domains:

Transport and mobility underpins all trade and logistics, from motorways carrying just-in-time manufacturing materials to last-mile delivery networks for e-commerce. Energy and grid systems must now handle a triple transformation: electrification of everything, computational loads from AI that will require 700 TWh by 2050, and integration of distributed renewable generation. Water and waste infrastructure faces climate volatility that makes century-old assumptions obsolete; what worked with predictable rainfall patterns fails catastrophically in the face of alternating droughts and floods (as Europe witnessed first-hand, with €18 billion flood damages in 2024 alone).

Defense and security installations have become urgent priorities after decades of underinvestment; NATO’s de facto 5% GDP target (Germany: 3.5% core defence, 1.5% supporting infra) means hundreds of billions in procurement. Social infrastructure (schools, hospitals, and public buildings where society actually functions) carries decades of deferred maintenance. Many European schools are over 100 years old, operating with infrastructure predating not only digitalization, but electrification itself. And binding it all together, digital infrastructure has evolved from ‘nice to have’ to ‘mission critical’: 5G networks, fiber optics, edge computing, and data centers form the operating system for every other domain.

These domains are no longer siloed. Data centers are an energy asset consuming as much power as a small city. An electric substation is a cybersecurity target. A bridge is a sensor platform monitoring structural health in real-time. Social housing is as much an energy system as shelter, with heat pumps and solar panels feeding back into stressed grids. Infrastructure today is an entire ecosystem, and ecosystems don’t crumble one component at a time… they collapse all at once.

2. The infrastructure value chain: Where technology creates leverage

Before diving into why €6 trillion will flow through European infrastructure, we need to understand the terrain. Infrastructure isn’t a market — it’s an ecosystem of interdependent actors, each with distinct incentives, constraints, and opportunities for technological transformation.

The main actors and their pain points

Asset owners sit at the top of the chain: public authorities managing transport networks, utilities operating energy grids, institutional investors holding real estate portfolios. They control €15 trillion in European infrastructure assets, but face an impossible equation: how to maintain aging systems, meet climate mandates, and modernize operations while public budgets shrink and performance requirements escalate. German municipalities alone face €159 billion in infrastructure backlogs. They desperately need solutions that extend asset life, reduce operational costs, and unlock private capital without losing control.

Developers and EPCs (Engineering, Procurement, Construction) transform capital into physical assets. Companies like BESIX, Vinci, and Strabag generate €400 billion annually in European construction but operate on razor-thin 2-4% margins. Their bottlenecks are structural: permitting timelines stretching 5-10 years, skilled labor shortages approaching 2 million workers by 2030, and productivity that hasn’t improved since 1995. They need technology that compresses timelines, replaces scarce labor, and improves margins without adding execution risk.

Operators manage infrastructure over a 30-50 year lifecycle, where 80% of total value gets created. Traditional operators, from *Deutsche Bahn to local municipal utilities, are trapped between old assets and new requirements. They must guarantee >99% uptime on systems where technology dates from the 1990s in the best case. Often core infrastructure elements like pipes, railway switches, and grid components are 50+ years old. Workforces retires faster than they can hire.

Financiers provide the capital that makes everything possible, but traditional infrastructure finance assumes concentrated, large-scale projects with predictable returns. The shift to distributed assets, e.g. millions of heat pumps instead of one power plant, breaks their models. Banks can’t efficiently underwrite €20,000 retrofits. Pension funds can’t directly invest in rooftop solar. The financing gap isn’t about capital availability (€3 trillion sits in European institutional funds) but about structuring mechanisms that transform distributed assets into institutional-grade investments.

Technological leverage

The real opportunity lies not in serving these actors individually but in deploying technology at the intersection points where value multiplies.

Planning and permitting automation represents a €50 billion annual bottleneck. Ark Climate operates at the critical intersection of digital infrastructure and climate-mandated transformation, building the operating system for municipal decarbonization. Their platform transforms how cities track energy consumption, plan infrastructure upgrades, and deploy capital toward climate neutrality. Prescient’s AI generates optimized structural designs that reduce material costs by 30% while automatically ensuring code compliance. Alice Technologies cuts construction planning time from months to days through AI-powered scheduling. These tools don’t just save time; they unlock projects that would otherwise never happen.

Robotics is directly tackling the labor crisis. With 45% of construction workers retiring by 2030, automation isn’t optional. Monumental’s bricklaying robots achieve €0.80 per brick versus €1.20 for human labor, a 33% cost reduction. But more importantly, whilst a human bricklayer works 6-7 hours maximum and requires union protections, the robot operates 24/7 without wage negotiations or sick days. This isn’t just about cost; it’s about availability. Robots show up when there are simply no human workers.

Digital operations platforms transform dumb assets into intelligent systems. Willow’s digital twins manage 420 million square feet by creating living models that predict failures, optimize energy use, and coordinate maintenance across portfolios. These platforms generate 30-40% operational savings while extending asset life by 10-15 years, turning OpEx savings into CapEx for new infrastructure.

Asset-backed finance unlocks the €4 trillion private capital gap. Hometree is more than just a heat pump installer; they create standardized financial products that pension funds can buy. Cloover transforms energy savings into creditworthy cash flows, expanding the addressable market by 40%. The leverage is massive: €10 million in equity can deploy €100 million in infrastructure through proper structuring.

Where margins hide and value compounds

The traditional view sees 2-5% margins in construction and assumes infrastructure is a bad business. This fundamentally misreads where value accumulates. Construction is just the entry fee; the real returns come from embedding into operations where software commands 70-80% gross margins, specialized engineering earns 25-35%, and long-term O&M contracts generate 20-30% returns that will compound for decades.

But the biggest opportunity isn’t in capturing existing margin pools – it’s in unlocking value that’s currently trapped. Automated permitting could release €500 billion in projects stuck in bureaucratic purgatory. Construction robotics doesn’t just replace workers; it unlocks 2 million job vacancies that would otherwise never be filled. Digital twins that extend asset life by 20% are worth €1 trillion in avoided replacement costs.

The companies that win won’t be those with the best individual technology. They’ll be those that position themselves where technology doesn’t just improve existing processes, but breaks open bottlenecks that have constrained the entire system for decades. They understand that in infrastructure, location in the value chain matters more than technological superiority.

3. Why infrastructure demand has reached a breaking point

The crisis of aging assets

The first force reshaping the sector is raw, unavoidable, politically explosive demand. The age of Europe’s infrastructure alone is a already a problem, but the larger issue is that the world around it has changed so dramatically that even „well-maintained“ assets no longer meet operational requirements.

Germany’s 40,000 bridges, most engineered for 1960s traffic volumes, now support logistics networks moving 3.5 times the weight at 10x the frequency. The 2024 Dresden bridge collapse wasn’t an anomal; it was a warning. Water systems designed for predictable weather patterns are failing under climate volatility. In 2024 alone, Europe suffered €18 billion in flood damages, with Valencia’s October floods killing 232 people and storm Boris affecting 2 million across 7 countries.

Housing shortages have turned into national political crises. Germany needs 700,000 additional apartments just to stabilize prices. The Netherlands faces a structural deficit requiring 900,000 new homes by 2030, while simultaneously 70% of existing housing stock needs deep energy retrofits to meet climate targets. The broader built environment (e.g. schools over 100 years old, hospitals with pre-digital infrastructure) carries maintenance backlogs measured in billions.

And then there’s energy. The European grid, designed for centralized generation flowing in one direction to passive consumers, must now handle millions of prosumers with rooftop solar, industrial heat pumps pulling megawatts, EV chargers creating evening demand spikes, and data centers requiring 99.999% uptime. The AI boom requires an estimated 700 TWh of power by 2050 — equivalent to adding another Germany to the grid. Germany needs €730 billion just for distribution grid upgrades until 2040. This isn’t modernization. It is reconstruction.

The capital wave

The second force is capital deployment at historic scale. For the first time since the Marshall Plan, Europe is mobilizing infrastructure spending that genuinely matches the challenge. By 2030, more than €2 trillion will be allocated through EU-level, national, and regional programs. But here’s the critical insight most miss: the actual infrastructure investment need reaches €6 trillion, leaving a €4 trillion private capital gap that public sources cannot fill. This isn’t a funding shortfall: it’s the largest investment opportunity in European history.

The money is already starting to flow. Germany’s Sondervermögen allocated €100 billion for defense modernization overnight, plus €500 billion for infrastructure and climate through special funds. The EU’s NextGenerationEU deployed €806 billion. National programs add another trillion across France 2030, Germany’s Climate Fund, Italy’s PNRR, and others.

Crucially, the rules of the game have fundamentally changed. Europe’s revised Construction Products Regulation harmonized standards across all 27 member states. The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), finalized in May 2024 with transposition by May 2026, mandates efficiency standards by 2030, creating a €1.5 trillion forced-renovation market. While some specifics may face future adjustments, the core deadlines remain binding law.

Climate adaptation has moved from planning to crisis management. The European Climate Risk Assessment identifies 36 major risks, with 21 requiring immediate attention. This creates a €344 billion annual investment gap just for climate resilience, transforming every infrastructure project with mandatory vulnerability assessments and adaptation requirements.

4. Private capital is already building tomorrow’s infrastructure

The market creates what governments cannot

For decades, European infrastructure was seen as the exclusive domain of the state. That era is over. Long before policymakers declared an emergency, private capital had already begun moving into the vacuum; not in speculative edge cases, but in core, mission-critical assets.

FlixMobility blazed the European trail, raising over $650 million at a $3 billion valuation to dominate Germany’s long-distance bus market — a market that didn’t exist until deregulation in 2013. Their masterstroke: acquiring America’s iconic Greyhound Lines for $78 million in October 2021, a 98% discount from its 2007 price. Within 18 months, they integrated it into their (technology) platform, creating North America’s largest intercity network with 2,400 destinations. FlixTrain extends the model to rail, operating private trains on public tracks, competing directly with Deutsche Bahn.

Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners raised €32 billion (more than many sovereign funds) specifically for energy infrastructure. They don’t just invest; they build and operate offshore wind farms, grid-scale batteries, green hydrogen facilities.

Octopus Energy manages 54 GW of renewable assets, which is more generation capacity than many national utilities. They aggregate millions of distributed resources into virtual power plants.

Energy infrastructure goes private

This is no longer about small distributed assets. When BlackRock acquired Global Infrastructure Partners for $12.5 billion, they weren’t buying a fund; they were buying the capability to own and operate tomorrow’s energy system.

The pattern repeats everywhere: Ember building private intercity electric bus infrastructure in Scotland. Lineas, Europe’s largest private rail freight operator, moving more cargo than national operators. Where public systems struggle with underinvestment, private operators emerge to fill the gap.

5. Learning from traditional champions: The infrastructure business model

Europe’s infrastructure incumbents have long understood something tech founders often miss: the infrastructure business model is not about construction. It is about long-term ownership, operations, and service revenues that compound over decades.

Vinci might invest €500 million building an airport, but over the 30-50 year concession, they’ll generate €10-20 billion from parking fees, retail concessions, real estate development, and landing fees. Construction earns them 5% margins; operations earn 40%.

Siemens Mobility doesn’t sell trains… it sells guaranteed uptime. The £1.5 billion Piccadilly line contract is just customer acquisition. The real value lies in maintaining those trains for 40 years, modernizing them every decade, and being the only vendor capable of integrating new systems. Once Siemens trains run on your network, switching costs become prohibitive.

Airbus and the Eurofighter program show the same logic. Initial aircraft sales represented 20% of the program’s €120 billion value. The remaining 80% came from decades of maintenance contracts, software upgrades, pilot training, spare parts at 70% margins, and data services that make the aircraft irreplaceable.

Three key lessons emerge:

- Entry through excellence, profits through entrenchment: Win the initial contract, then become so embedded that replacement is unthinkable.

- The infrastructure multiplier: Every €1 of construction creates €10-20 of operational value over the asset lifecycle.

- Compound advantage: Each year of operations generates data, relationships, and switching costs that make the incumbent stronger.

6. The new playbook: What Helsing and Anduril reveal

If traditional giants provide the business model blueprint, the new infrastructure leaders show how technology reshapes the playing field — but not in the way most expect.

Helsing, Europe’s defense AI breakout, didn’t succeed through superior algorithms alone. They understood that defense ministries don’t buy neural networks; they buy trust, sovereignty, and capability wrapped in institutional comfort. Helsing built AI that performs in battlefield conditions where connectivity fails. But more critically, they built a company that feels institutional: hiring former military officers, integrating with 40-year-old NATO protocols, accepting multi-year sales cycles.

Anduril took a different path that’s equally instructive. They built autonomous systems first and navigated procurement second, letting performance speak louder than PowerPoints. But what they actually built wasn’t just drones, it was a software platform (Lattice) that integrates with existing systems while gradually taking over more functions. They’re building a defense operating system that becomes more valuable as it connects more assets.

Both companies demonstrate advantages that Silicon Valley can’t replicate:

- Regulatory fluency as moat: Understanding ITAR, NATO standards, or sovereignty requirements isn’t overhead – it’s competitive advantage

- Trust as currency: Every successful deployment builds trust that no venture funding can buy

- Patient capital for patient markets: Infrastructure sales cycles don’t fit quarterly metrics

- Talent arbitrage: Former officers and utility executives bring billion-euro relationships

7. The Trillion-Euro housing (water/energy) case study

Why traditional construction cannot solve the crisis alone

The European housing crisis crystallizes every infrastructure challenge. Traditional construction hasn’t improved productivity in 30 years. Labor scarcity is structural: 45% of construction workers retire by 2031, with no replacements. Permitting adds 7-10 years in major cities. Construction costs rose 40% since 2020.

Katerra’s $2 billion collapse seemed to prove infrastructure tech doesn’t work. But Katerra’s failure was about timing and approach. They tried vertical integration in 2015 when robotics cost too much and AI couldn’t handle complexity; they targeted fickle B2C/B2B markets rather than stable B2G contracts. Most fatally, they tried revolutionizing from outside rather than working within frameworks.

What actually works now

Today’s winners learned from Katerra’s mistakes.

ecoworks augments construction through systematic retrofitting, achieving 30% EBITDA margins while cutting time by 50%. They focus on existing buildings, where 80% of 2050’s housing stock already stands.

Monumental deploys robots alongside human crews. At €0.80 per brick and 24/7 operation, they solve both economics and labor shortage simultaneously. They don’t sell robots; they charge per brick laid, aligning incentives with outcomes.

ICON’s 3D-printed neighborhoods prove the technology, but their breakthrough is securing multi-year government contracts that provide patient capital for innovation.

The European opportunity

Europe’s modular construction market will double to €85 billion by 2030. Factory OS and TopHat deliver thousands of units annually. Construction robotics funding hit €1.36 billion through Q3 2025 (up 125% year-over-year).

Smart building systems represent a €31 billion opportunity by 2032, growing at 29% annually. Every building becomes a data platform, continuously optimizing energy use and predicting maintenance.

Climate resilience adds urgency. The Netherlands is upgrading 887 kilometers of dikes. Spain allocated €50 million for Valencia’s grid climate-proofing. Every project now requires vulnerability assessments, creating forced upgrade cycles across the built environment.

8. Why this will look like an inevitable transformation

The hardest part of infrastructure innovation isn’t the technology — it’s the convergence. You need AI that handles construction dust, robotics economically viable at scale, sensors cheap enough for every concrete pour, software that integrates with 40-year-old systems.

That convergence just happened.

Five technology curves crossed viability simultaneously. Computer vision identifies defects better than inspectors. Robotics costs dropped 80% since 2015. IoT sensors became economical for comprehensive monitoring. Edge computing enables real-time processing. Large language models parse byzantine regulations, making compliance programmable.

The market pull is irresistible. €6 trillion in needs based on asset age, climate requirements, and load growth. Construction workforce shrinking 20% through 2030. Energy efficiency mandates with legal deadlines; buildings not meeting 2030 standards face shutdowns, not fines.

The competitive dynamics favor new entrants. Traditional contractors with 2-3% margins can’t invest in R&D. Infrastructure operators, constrained by procurement rules and unions, can’t experiment. Incumbents are structurally unable to lead their own disruption.

Willow, managing 420 million square feet, shows what winning looks like: becoming the building’s operating system, reducing energy by 33% whilst predicting failures. ClimateX, backed by Google Ventures, built „Google Maps for climate risk,“ with 94% of revenue from business decisions rather than compliance.

A decade from now, we’ll look back at 2024-2026 as the critical inflection point. Today’s funded companies will establish category leadership. Within 10 years they’ll be the infrastructure layer: the Vincis and Airbuses of the physical-digital era.

9. The financial architecture:

How €2 trillion becomes €6 trillion

Beyond traditional project finance

If technology and regulation explain why this is Europe’s moment, financial architecture explains how it scales. Traditional finance assumed massive, concentrated projects funded through bonds with 20-year horizons. Modern infrastructure is distributed, requires faster deployment, and generates different cash flows.

The secret sauce lies in decentralized asset-backed financing: structured products grounded in real assets generating predictable cash flows. Pool thousands of small assets into portfolios behaving like traditional infrastructure investments; structure them with different risk-return profiles. Pension funds buy safe senior tranches; hedge funds take higher yields. Developers recycle capital to build more.

Asset-backed financing 2.0

Theory became reality when Enpal pooled 8,469 solar installations into a €240 million security. The EIB and EIF didn’t just approve; they anchored it. Hometree aggregated 35,000 heat pumps into institutional-grade assets with £300 million in facilities. Cloover raised $108.5 million treating energy savings as creditworthy cash flows.

€850 million flowed through these structures in 2024-2025 alone. Bees & Bears secured €500 million from an ECB-supervised bank, the largest institutional commitment to European climate fintech.

The US precedent shows the trajectory: SolarCity’s $54 million securitization grew to $20 billion annually by 2020. Europe follows faster due to urgent need and supportive regulation.

Why this changes everything

The clever combination of knowledgeable venture capital and asset-backed financing multiplies capital. €10 million in equity deploys €100 million in infrastructure through 10x leverage. Terra One proved this, turning €10 million equity into €750 million deployment capacity: a 75x multiplier.

It aligns everyone’s interests. Governments get infrastructure without budget impact. Institutions access yields above bonds with infrastructure-like risk. Consumers receive upgrades with no upfront cost. Startups scale without dilution.

Every heat pump installed through embedded finance, every building retrofitted through performance contracts… these become raw material for tomorrow’s infrastructure securities. Companies building these assets aren’t just construction-tech startups. They’re creating collateral for a multi-trillion-euro asset class.

10. What it takes to win in infrastructure

Success requires mastering three games simultaneously. Excellence in just one or two areas guarantees failure.

The technology game

Your robotics must operate in rain, snow, 40-degree heat. Your software must integrate with Siemens PLCs from 1995 and Schneider systems from 2020. Your sensors must survive 20 years embedded in vibrating concrete. But technical excellence is table stakes: everyone achieves parity. Winners are decided by the other games.

The trust game

Infrastructure runs on trust earned through years of consistent delivery. Governments don’t buy from startups, they buy from partners. This means understanding 18-month RFPs, knowing the deputy director makes decisions, hiring the engineer who wrote the standards.

Octopus Energy hired hundreds of former British Gas employees bringing regulatory relationships. Your first project is a pilot. Your tenth proves capability. Your hundredth makes you infrastructure.

The economics game

The winning model isn’t selling equipment; it’s embedding into 30-50 year asset lifecycles. Cosmo Tech charges €500,000 annually to save €5 million in rail maintenance — 10x ROI compounding forever. Create recurring revenue through operations. Build switching costs through integration.

When all three games reinforce each other, the flywheel accelerates until you become infrastructure that’s impossible to dislodge.

11. Why PT1 is uniquely positioned

Infrastructure doesn’t respond to capital like software does. You need legitimacy, access, and operational intelligence from builders. A new breed of venture capital that speaks the language of atoms, not just bits, and knows that the difference matters.

The Power of Industrial LPs

PT1’s advantage stems from our wide LP base: European industrial power.

Traditional heavyweights such as Strabag and Besix remain critical in delivering the physical backbone of Europe. But they are increasingly joined by ecosystem partners like Goldbeck and Drees & Sommer: Goldbeck as one of Europe’s most advanced industrialised builders, and Drees & Sommer as a key planner in shaping what the ‘new infra world’ will look like across energy, mobility and digital systems.

On the capital side, Helaba and Commerz Real play a pivotal role in financing the next generation of long-dated assets, from energy infrastructure to advanced logistics and grid-connected systems. And global advisors such as JLL help translate these developments into institutional capital flows, connecting operators, investors and policymakers across markets.

When those multi-national powerhouses introduce portfolio companies, procurement doors open that are forever closed to Silicon Valley. Our industrial LPs and co-investors control physical supply chains.

Orchestrating complex capital

Terra One illustrates what this means in practice. Battery storage economics are simple in theory, but impossible to finance through traditional venture capital.

PT1’s initial seed proved the technology. But the real ‘unlock’ came from supporting the founders to structure and optimize a full financing stack. LPs committed €100 million in asset financing, unlocking €150 million mezzanine from Aviva Investors, triggering senior debt from infrastructure banks. Result: €750 million deployment from €10 million initial investment.

ClimateX, another portfolio success, raised $18 million from Google Ventures for their climate risk platform („Google Maps for climate risk“). They analyze 1.5 billion assets globally, with 94% of revenue from business decisions, proving climate intelligence drives revenue, not compliance.

The operating system for infrastructure innovation

Our venture partners are operators. Klaus Freiberg ran Vonovia’s 550,000 apartments. Timo Tschammler led JLL Germany. Michael Lowak built Getec to €1 billion before selling to JP Morgan, Sander von de Ridjt scaled Planradar from cosy Austria into 75 countries around the globe.

This manifests in portfolio success:

Voltfang structured €250 million financing for Europe’s largest second-life battery facility.

AskVinny puts asset management on autopilot. Their AI agents reduce overhead while improving occupancy rates and tenant experience. Win-Win-Win.

12. Europe’s infrastructure moment: The window is open now

Europe is rebuilding itself. This isn’t speculation. It’s mathematical certainty based on asset age, climate requirements, and technological readiness.

The EU’s Renovation Wave touches 35 million buildings by 2030. Germany committed €2 billion annually for climate-friendly construction. Every nation has similar programs, all desperate for execution capability traditional contractors can’t provide.

The regulations are passed, money earmarked, deadlines looming. The question is, who captures the value? European companies understanding context, or foreign giants moving faster?

History shows that new champions emerge when infrastructure shifts dramatically. Companies dominating coal-age infrastructure didn’t lead the oil age. Builders of copper networks didn’t create fiber optics. Traditional construction giants with 2% margins won’t lead intelligent infrastructure.

The convergence is unprecedented:

- Technology working in the physical world at economic prices

- €2 trillion committed against €6 trillion needs

- Climate resilience urgency with €344 billion annual gap

- Regulations mandating digital-first approaches

- Workforce crisis making automation essential

- Private capital ready to fill government gaps

Europe’s unique advantages, e.g. engineering excellence that built the world’s best infrastructure, regulatory sophistication creating frameworks others copy, industrial heritage understanding complex systems, and patient capital thinking in decades, provide the ingredients for new global infrastructure leaders.

The founders building today are defining the next industrial era. Some retrofit millions of buildings with AI-optimized systems. Some deploy robots building faster and cheaper than humans. Others create financial platforms transforming scattered solar panels into institutional assets.

These companies will establish category leadership in coming years. Within a decade, they’ll be the infrastructure layer itself. The transformation window extends far into the future, but foundations for the winners are being laid now.

This is Europe’s infrastructure moment.

The clock has already started.

Sources for verifiable facts

- Flood damage and fatalities in Europe’s 2024 storms – Reuters and Euronews report that 2024 storms and floods in Europe affected ~413,000 people, caused at least 335 deaths, and resulted in at least €18 billion of damages . The October 2024 Valencia floods alone killed 232 people and caused €16.5 billion in losses.

- Data‑centre electricity demand – Wood Mackenzie notes that data centres are set to consume around 700 TWh of electricity in 2025, more than double current consumption, and that demand could rise to 3,500 TWh by 2050 .

- German municipal infrastructure backlog – Germany’s KfW municipal panel estimated the municipal investment backlog at around €159 billion .

- Lifecycle costs – The Whole Building Design Guide states that roughly 80 % of a facility’s lifecycle costs are associated with operations and maintenance, underscoring the importance of O&M over construction costs .

- European construction labour shortage – The International Trade Union Confederation predicts a 2 million‑worker shortage in Europe’s construction sector by 2030, combining new demand and the replacement of retiring workers . Additionally, U.S. sources (NCCER) expect 41 % of the U.S. construction workforce to retire by 2031 , illustrating similar demographic pressures.

- Low margins in construction – Financial data show the engineering and construction sector has an average net profit margin of ~4.5 %, confirming that construction operates on thin margins .

- Germany’s €500 billion special fund – The German Federal Ministry of Finance explains that Germany’s special fund for infrastructure and climate neutrality totals €500 billion, including €300 billion for federal investments, €100 billion for the Climate and Transformation Fund, and €100 billion for Länder and municipalities .

- EU climate‑risk assessment – The European Environment Agency’s climate‑risk assessment identifies 36 major climate risks, and more than half need more action, with eight risks needing urgent action .

- Climate investment gap – The I4CE report “State of Europe’s climate investment” states that EU climate investments must reach €842 billion per year between 2025 and 2030 to meet climate goals; with actual investment at €498 billion in 2023, this leaves a €344 billion annual investment gap .

- France 2030 plan – The French government’s “Understanding France 2030” site details that the plan allocates €54 billion for projects, with 50 % targeting decarbonisation and 50 % supporting emerging industries . It works alongside the €100 billion France Relance recovery plan, of which around €40 billion comes from EU support .

- Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) – Intesa Sanpaolo notes that Italy’s PNRR allocates €235 billion, including €191 billion from the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility, €13 billion from REACT‑EU, and €31 billion from a national fund .

- EU grid investment needs – An EU guidance document says that EU‑wide distribution grids require about €730 billion in investment by 2040, with transmission grids needing €477 billion .

- Housing shortages – LBBW research describes Germany facing a housing shortfall of more than 700,000 homes , while a study for Germany’s housing ministry concludes that 320,000 new apartments must be built annually through 2030 to meet demand . The European Commission’s RRF page for the Netherlands notes that the Dutch government aims to build 900,000 new residences from 2022‑2030 .

- Europe’s building stock – The World Economic Forum writes that over 35 % of Europe’s buildings are more than 50 years old and nearly 75 % are considered energy‑inefficient .

- Responsibility for bridges in Germany – The Associated Press reports that federal authorities are responsible for about 40,000 bridges in Germany .