Decarbonising multi-family homes is hard

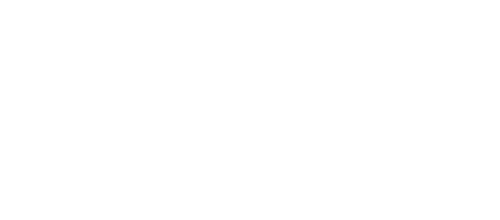

Real estate is carbon-intensive. Operating and constructing buildings makes up 40% of the EU’s energy consumption – and the majority is from operations. All realistic net-zero pathways have decarbonising buildings as a central part. But we’re behind target. The residential retrofit rate in Germany has hovered at 1% of housing stock for the last few years. At this rate it will take over a century to decarbonise residential buildings alone (way beyond our targets).

Slower than expected residential retrofits are a global problem, but Germany has some unique challenges: multi-family homes.

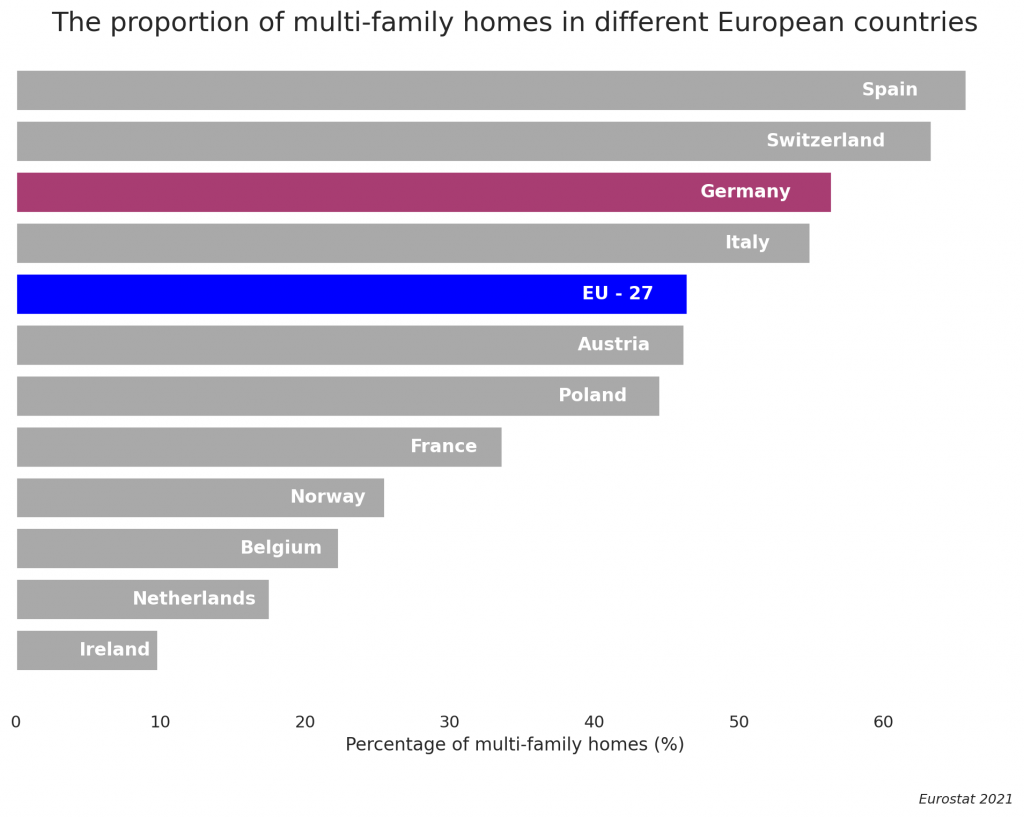

Berlin has these concrete jungles of Plattenbauten, which owe their existence to post-war East Germany. At the time, with very little remaining housing stock, building en-masse was the only solution to meet surging housing demand. The legacies of these choices linger today, with Germany having one of the highest multi-family rates in Europe.

The EU27 average for multi-family homes is 46.4%, whereas Germany is at 56.4%. The problem with multi-family is that it is harder to decarbonise. These buildings have complex ownership structures, diverse building typologies, opaque energy data and potentially warring stakeholders.

Barriers to decarbonisation

So how can we fix this? One approach would be to tear them all down and replace them with brand new perfectly designed buildings. This is not feasible (economically and ecologically). Instead, we need to rely on existing methods.

A popular method is to make structural and fabric improvements. This has traditionally been more challenging for multi-family buildings due to the misalignment between the tenants and the landlord. Why would a landlord pay a significant amount to benefit the tenants? Our portfolio company ecoworks is working to fix this. They retrofit buildings at scale by applying a proprietary secondary building skin.

ecoworks‘ solution works for multi-family homes for two main reasons. Firstly, disruption is minimal. Tenants are not forced to live elsewhere, a cost which the landlord would have to cover. Secondly, their approach is faster and cheaper than traditional retrofit. This reduces the burden on landlords. Getting the retrofit cost down is helpful, but why would a landlord want to invest anything at all that exclusively benefits their tenants.

We believe this incentive gap is the biggest barrier to building decarbonisation. Governments believe so as well and are taking action to fix this. The German government has gone for a stick rather than a carrot. Regulations on EPCs are forcing landlords to retrofit these older buildings. ecoworks is an easy answer for landlords to meet these regulations.

There are other ways to incentivise landlord investment. Some ecoworks concepts involve placing a new modular storey onto the top of the building (depending on the roof type), which significantly increases the net internal area of the building. This can increase future rental yields, boosting cap rates for the larger institutional landlords.

In addition to structural work, landlords can add local renewable generation capacity, which is less carbon intensive than the grid. This has traditionally been more challenging for multi-family. One of the primary challenges is the significant upfront cost, which again brings us back to the incentive problem. Another challenge is related to the limited rooftop space available in multi-family buildings. Multi-family typically has a lower solar potential / energy usage ratio. This intuitively makes sense: We could convert a large house into three flats, and now we’d have three fridges, three TVs, potentially three hot water systems, etc. Multi-family buildings are much more energy intensive on a per squaremeter footprint basis. This means that one rooftop solar system may not generate enough to support the entire building’s residents. While the building’s proportion of self-consumption (the percentage of energy generated used by the building itself; rooftop solar on single-family is around 70%) would be higher, solar cannot replace secondary power from the grid. Another complication is understanding how much each tenant pays, and for what.

The tenant electricity framework

The “tenant electricity” framework is one way of resolving these issues. This framework allows energy assets to be installed on apartment buildings. The energy is then sold to tenants, with any surplus going to the grid. The landlord pays for the improvements, but benefits by selling the energy generated. This fixes the incentive problem. These models are also beneficial for tenants. Tenants enjoy cheaper energy as their landlord must sell at a 10% discount to local utilities.

There are two tailwinds in this framework’s favour. Firstly, several German grid operators have announced a doubling in the base transmission costs. Tenant electricity is exempt from this (as the power doesn’t go through the grid). Tenant electricity is becoming a lot cheaper than grid power.

Secondly, Germany’s new legislation, Solar Package 1, minimises the hurdles for landlords to set up these tenant electricity frameworks. As an example of classic German bureaucracy, the tenant electricity framework discussed above didn’t really exist. Prior to this legislation, an official third party was needed in the relationship. This third party would guarantee the electricity for the tenants. However, setting these relationships up was complex: There are even startups which exist solely to do this. The new legislation strips away a lot of the bureaucracy, cutting out the need for a third party and making the framework definition from above a reality.

One of the startups operating in this space is Einhundert. Einhundert targets real estate companies and enables them to roll-out tenant electricity in their entire portfolio by covering every step one needs to take along the way while starting with tenant electricity: property analysis, solar panel installation, smart metering and cloud-based software for monitoring and predicting energy consumption levels. They’ve been growing steadily, showing an increasing demand for these frameworks. They were founded before the regulation changes, and it’ll be interesting to see if their business is impacted by the process becoming simpler. Is Solar Package 1 an existential risk to their raison d’être, or are they not affected?

Another startup in this space is the Dutch company, IBIS Power. IBIS takes an entirely different approach. They don’t focus on the legal and infrastructure barriers behind tenant electricity. Instead, they provide a modular unit called the PowerNEST, which goes on top of high-rise buildings. The PowerNEST is a mixture of solar and vertical wind turbines and is designed to generate as much electricity per squaremetre as possible. In some cases, depending on local geography, one PowerNEST can generate enough energy to support the entire building’s usage. But without the tenant electricity framework, IBIS and their superior hardware suffer from the same fundamental issue: Why should a property owner pay six figures for something which has zero upfront benefit to them.

These are just a few examples of companies which are helping multi-family buildings decarbonise. Tracking their funding over the last 18 months, we see significant amounts of capital going into this space (ecoworks raising €40m last year and Einhundert raising €6m ). Clearly this space is growing, and we might start to see that retrofit rate slowly increasing. The tenant electricity framework is a great approach to resolve the alignment gap. However, we’re open to other ideas as well – if you know someone building the future in this space please introduce us.